Don't Let Them Disappear the Beautiful

an Andalusian musing

I once read that New York is as much a part of you after 5 minutes as 5 years. It’s an immediate osmosis - a place so teeming with life yet so antithetical to the natural that these undulating contradictions and extremes accost your synapses and you are forever changed.

Not everyone is susceptible of course. Some people steel themselves against inspiring environments despite instagram posts to the contrary, like the American couple drinking Starbucks in Cordoba complaining of “inconvenient” mealtimes. But if you let it, some places will steep to become part of you, and your perception.

Of course, Cordoba is much different than New York. Here it is not the contradictions of nature but the contradictions of time and symbiotic cultures that change you.

In southern Spain, I visited Cordoba, Granada and Toledo as part of an ancestral jaunt with my father. Branches of his/our family tree root back to southern Spain where they were ousted after the Edict of Expulsion was signed in 1492, a decree that expelled the Muslims and Jews of Spain, kicking off the Inquisition and decimating hundreds of years of cultural vibrancy under Muslim rule. It was a sort of repeatable final solution, not least because, as human dumbshittery would have it, Ferdinand and Isabella signed that decree a mere few days before Columbus set sail on his genocidal enterprise.

The Edict was signed in Granada, at the Alhambra, a 13th century Muslim palace and fortress complex that’s about a 45-minute and 45 degree hike up from the old town center. The gardens are gorgeous, the architecture a captivating blend of curved and pointed artistry where Arabic dances across the walls in stories I can’t read but feel are somehow a part of me.

About a two hour train ride away, the Alcazar in Cordoba is just steps outside the Juderia, the Jewish quarter, about a five minute walk from the statue of Maimonides, the 12th century Jewish philosopher and physician to Saladin, the Muslim Sultan who finally ousted the crusaders from the holy city of Jerusalem. The Alcazar was once al-Qasr or “palace” - home to public baths, gardens and the largest library in the West, a jewel in the crown of al-Andalus. In the 1480s, the Alcazar was turned into a torture camp by the Catholic rulers Ferdinand and Isabella. The Alcazar was not only one of the headquarters of the Inquisition, it was also where the Spanish monarchs first met with Christopher Columbus.

I try to imagine my ancestors going to the Arab baths, wandering the aisles of books with the same eager smiles that I now have in libraries and bookstores. I imagine philosophical conversations in the gardens where Arabic irrigation methods nurtured life beneath a Spanish sun. I try not to imagine the baths made into torture chambers. I try not to imagine the screams that recoiled off of walls that had once heard laughter. I try not to focus the terror. As misanthropic fate (or our monkey brains) would have it, it’s easier to strip a place of joy than of pain. But I can’t let them disappear the beautiful.

We just happened to arrive in Toledo a couple of days before the Festival of Corpus Christi (body of Christ). The streets were lined with flowers and fabric, random flares of music off of cobblestone. Giant puppets stood in the grand square of the Cathedral ready to once again “walk.” There was a rabbi in Arabized dress, what looked to me like Muslim rulers in decorated robes, and of course Christian effigies. I stepped into a small shop to buy some water and a paper fan. The woman in hijab who ran the store was speaking Arabic on the phone. I walked up to pay and asked in Spanish what all decorations were for. I couldn’t help but smile at the thought of a Muslim woman telling a Jew about the festival of the body of Christ. But if it makes sense anywhere, it makes sense in Toledo.

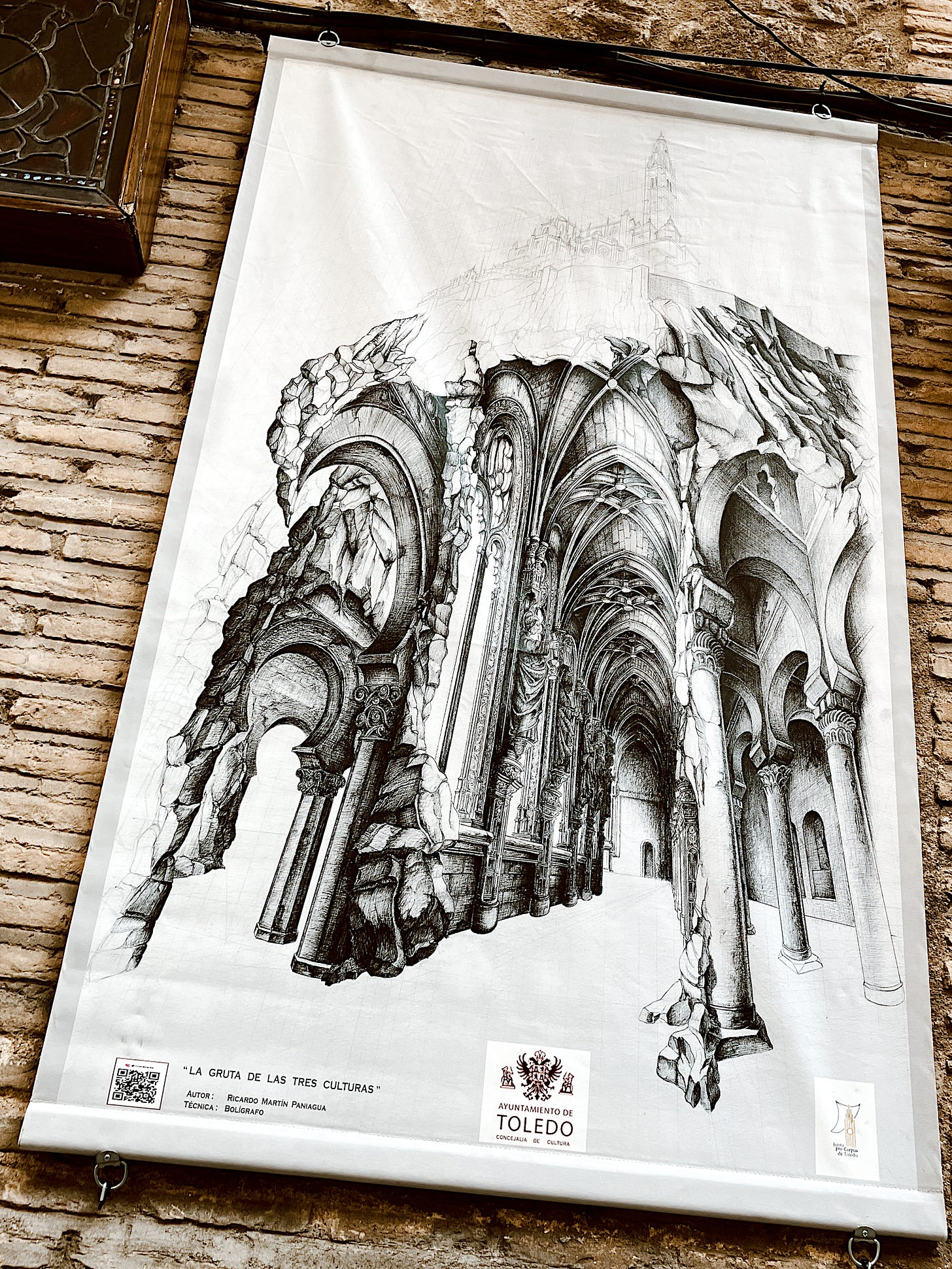

Down one street, art prints hung like ornamental flags on the walls. I stopped in front of one striking black and white piece called La Gruta de Las Tres Culturas, the cave of the three cultures.

In his description of the piece, local Toledo artist Ricardo Martin Paniagua writes (translated from Spanish, please excuse any errors), “Deep within this rocky promontory on its seven hills lies the city of Toledo. Legends speak of its…caves and rivers beneath the ground…I wanted to reflect three grottoes within…representing the Christian culture is the Gothic cloister of the Monastery of San Juan de los Reyes in the center; the Jewish culture is represented by the interior of the Synagogue of Santa Maria la Blanca, and the Muslim culture is represented by the Mosque of Cristo de la Luz on the right of the painting. The three interconnected grottoes represent that ‘whole’ of intercultural coexistence that evokes that time of tolerance in which Toledo housed these three great cultures in its streets…”

The first thing you might notice is that both the Synagogue and the Mosque have hilariously Christian names. The former being named Saint Mary the White, and the latter Christ of the light. Incidentally, both of the ancient synagogues in Toledo are on Calle de los Reyes Catolicos, the street of the Catholic Kings. One could say that it’s simply the privilege of the victor to name his spoils, but this is more nuanced than that.

When Ferdinand and Isabella came to power, they wore Arabized dress and claimed they had no interest in alienating their Muslim and Jewish countrymen. When you walk through La Mezquita de Cordoba, the Mosque Cathedral, the sprawling candy-cane doilied arches are so blatantly Arabic that it can come as quite the shock when you see the trappings of Christianity like Mary, Jesus and the cross peppered throughout. But only if you’ve been steeped in the homogenous marinade that is the mother’s milk of Western hegemony and white supremacy. As María Rosa Menocal writes in her brilliant book Ornament of the World:

“So deeply rooted were the old Andalusian habits that it was only with great violence over more than a century, with the burning of thousands of libraries and with the insistent propogation of even-then risible notions of the racial purity of Christians, that the Spaniards were finally cured of their deeply entrenchned ‘medievalness.’”

I’m a sentimental sop but it made me smile cry to see the parade of Muslim, Jewish and Christian puppets, to see the buried braids of history on display, the caves that hold up a city that dares us to forget how we could be because we were.

I have no illusions about that past as utopian. After all utopia literally translates from Greek to “no place,” and I am not one to look for what can’t be found. The so-called Muslim Golden Age was also a time of political and economic turbulence. Cities changed hands like cards in a drunken poker game. Muslims, Jews and Christians didn’t get along all the time nor did they always choose teams based on religion. Shit was messy and unstable. And there were also public baths, and gardens and libraries. There were also brilliant cultural exchanges, poetic triumphs, the birth and rebirth of languages. There was so much beauty. There is so much beauty. But so much of it is buried, literally and figuratively. Buried in caves, in graveyards, in layers of dirt and dust. Buried in shame and the failure to safeguard, buried by censorship and a forced forgetting. Buried alive. May it haunt us. If ghosts exist from the telling, let us never stop telling these stories. Let us let ourselves be changed by them, belong to them, carry them.

Let us never forget that we have steeped our bodies in ritual baths instead of blood. We have treated our minds to kinetic cultures rather than narrow and violent idiocy. We have embraced contradictions rather than fearing them, letting them dangle like tzitzit from our synapses, unkempt and sacred. It may be that we have buried the beautiful like a treasure to keep it safe. But don’t let it disappear. Don’t let them disappear it.

Love this piece, these places and the remembering. Thank you for capturing it all so beautifully. (You inspired me to find my selfie with Maimonides.)

Oh gosh this piece made a ‘sentimental sop’ of me. Haunting and beautiful and took me back to these places and their history