My viewpoint, in telling the history of the United States, is different: that we must not accept the memory of states as our own. - Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States

Sometime in February (reports differ on the date), the National Park Service’s (NPS) page titled “What Is the Underground Railroad” got a makeover. The large image of Harriet Tubman was gone, along with a quote of hers. Instead, the page showed some commemorative stamps of white and black abolitionists with the wording “black/white cooperation, flight/faith, defiance/hope” and other random words seemingly taken from an inspirational Etsy pillow.

Now it’s reverted back. Isn’t that nice?

I’ll save a commentary for how fragile the digital archive is for another time. My focus here is really how we shouldn’t be trusting the state to tell Harriet Tubman’s story in the first place - or that of anyone who fought for liberation. The job of the NPS like any state-run institution is to tell the story of the nation-state known as the United States, as constructed by that nation-state. It is to uplift the voices of the people (mostly dead white dudes) whose names we already know because they’ve been drilled into us since we were old enough to have a poster of Presidents on our classroom wall. Question: did y’all also get a lollipop in 4th grade for reciting them all from memory? Could you still do it today? So was that at all a useful task or attempt at conveying history? OK, moving on.

Tubman wasn’t the only target of the latest digital tirade. Baseball great Jackie Robinson, Navajo Code Talkers, women, LGBTQ+ folks, and buckets of other people who aren’t male or white have been taken down from government sites. While some, like Tubman, have been put back, at least momentarily, I thoroughly reject the idea that these sites were somehow keepers of those legacies, protectors of the histories of the oppressed.

Now, I’m not saying we should accept or normalize the takedown of these sites and this information. Some of the pages and data taken down are vital for research and projects that center and uplift the lived experiences of people who aren’t cis straight white dudes. But just as we should not accept the rise of fascism, we also can’t pretend that it’s something aberrant from the “land of the free.” Contextualizing is not excusing. Contextualizing is not normalizing.

In short, we have never been able to rely on the nation-state to keep or tell the stories of the people. Indeed, for the sake of its own preservation, it can’t. A nation-state is a series of myths formed and perpetuated atop a violent bordered genesis which necessitates the internal control of some, and the violent othering and expulsion of others. The lived experiences of the people on whom that nation-state stands are not only not of interest to the nation-state, they are dangerous.

The roar of the people’s history told from the ground up splinters myths, shakes foundations, rattles thrones and threatens to topple empire. It exposes the fragility of a system built atop organized forgetting and assumed powerlessness. If we remember, if we tell, who among us would still choose to uphold the myths that oppress us?

As Terry Steele, a former mine worker, UMWA member, and star of my documentary, Hard Road of Hope put it, “It’s grassroots organizing when you tell your history.”

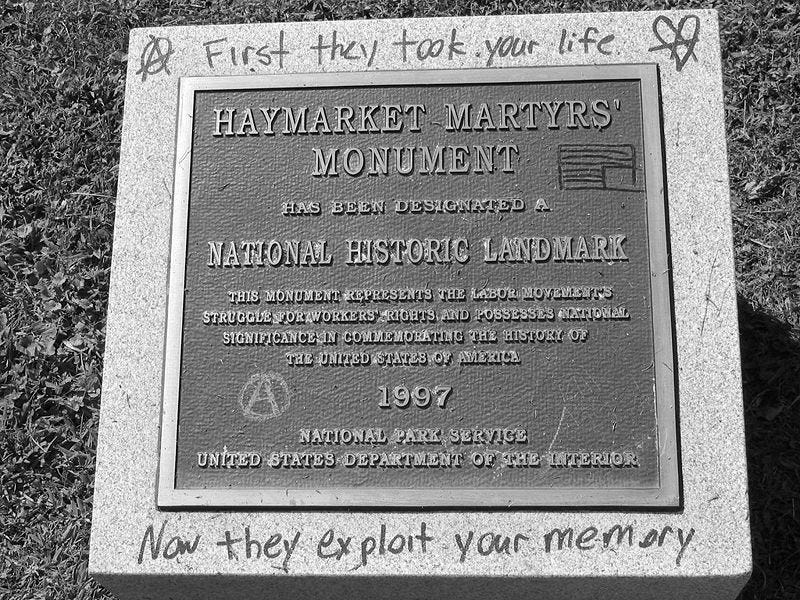

One very apt, and upcoming example is May Day. Internationally recognized as a Labor Day to unite workers across borders and boundaries, this day commemorates an event that happened right here in the US of A. Known alternatively (depending whose side you read it from) as the Haymarket Affair, the Haymarket Massacre, the Haymarket Tragedy or the Haymarket Riots, things kicked off on May 1, 1886 when after years of organizing, thousands of workers across the country went on strike demanding an 8-hour workday. Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will was the basic gist. Absolutely extremist, no?

Needless to say the powers that be didn’t like this so police and private militias a la the Pinkertons went to work. On May 4, 1886, a rally was held at Haymarket Square in Chicago following the murder of four strikers the day before. After a few speeches, nearly 200 police barged in demanding that the crowd disperse. Organizers responded by saying that the meeting was almost over. Suddenly, a bomb exploded in the swarm of police, wounding sixty, seven of whom later died. Police responded by opening fire into the crowd, killing several and wounding hundreds. Although it is unclear where the bomb came from and who detonated it, it is quite clear who bore the blame. Eight anarchists were tried and found guilty, only two of whom had even been present at the rally. One committed suicide, three had sentences commuted to life in prison, and four were hanged. Following Haymarket, martial law was declared. Labor organizers, journalists and allies were targeted, and the effort to deride and defame anarchists, socialists, communists, and labor organizing in general escalated, continuing to this day.

I was never taught this in school, and I imagine you weren’t either. If you were told anything about May 1st, perhaps you were told that it’s officially known as Law Day. I’m serious. In 1958, President Eisenhower proclaimed May 1st as Law Day, “a day to recognize the importance of the rule of law in a free society.” Ahem. A bit on the nose, don’t you think, Ike?

In the closing statements of his absurd trial in October, 1886, one of the condemned men August Spies said,

“Have we broken any laws by showing to the people how these abuses, that have occurred for the last twenty years, are invariably pursuing one object, viz: to establish an oligarchy in this country so strong and powerful and monstrous as never before has existed in any country?”

In terms of breaking an official law, no. In terms of breaking the unofficial law of empire, oh yes. And he was hanged for it. Far from hyperbole, the prosecution said as much: “Anarchy is on trial." "Hang these eight men and save our institutions."

The unwritten laws of empire are shrouded by official aphorisms like “all men are created equal” as they uphold the slavery, genocide, misogyny, and capitalist violence upon which this country was founded.

Today, we see as James Baldwin once wrote, “that history is not past.” To take but one of many examples, while Mahmoud Khalil’s lawyers argue for his freedom in the courts, the fact is that he was kidnapped not in accordance with US law but rather with US practice. He’s being held in prison facing deportation for the crime of disagreeing with US policy, a playbook used many times in the past, from the Palmer Raids to the LA8. Of course he should never have been in this situation, not just according to common sense and humanity but also according to US law.

But again, the official laws of empire are only there as the gay pride flag on City Hall, the Black Lives Matter painted on the street leading up to the White House, the Harriet Tubman on the website. They are there to give the appearance of a nation of, for and by the people, of laws that protect our rights. But they, like the official history, are a farce. They are twisted or even outright rejected when it suits US policy. The empire must always protect itself, and part of doing that is ensuring that we, the people don’t know who we are, and that we don’t know what our state actually is.

The people who kidnapped Mahmoud, the people who hanged August, the people who tried to lynch Tubman, these are not the people we should look to for accurate accounts of our history or our present. Indeed, I’ve always found it odd that people who don’t trust their governments to tell them the truth of the present somehow trust them to tell the truth about the past. This is a clear misunderstanding of what history is.

History is not the poster of dead white dudes on a wall, and learning it is not being able to name them. History is a map. It orients us so we understand where we’ve been, where we are in the present so that we can forge a path for the future. It is one of the necessary tools we must sharpen in order to get out of this death-making labyrinth known as the US.

Without history, the present times aren’t just scary because they’re fascist, they’re scary because they are totally unknown. By learning a history grown from the roots, we see not only that we’ve been here before, but that we’ve refused to shut up and sit down before. And we see the cover-up of grassroots history as a necessary step in perpetuating empire.

As Assata Shakur wrote, “Nobody is going to give you the education you need to overthrow them.”

To put it another way, as George Engel, another one of the condemned men after the Haymarket Massacre said in his address to the courtroom,

“All that I have to say in regard to my conviction is, that I was not at all surprised; for it has ever been that the men who have endeavored to enlighten their fellow man have been thrown into prison or put to death…I say: Believe no more in the ballot, and use all other means at your command. Because we have done so we stand arraigned here today – because we have pointed out to the people the proper way…My greatest wish is that workingmen may recognize who are their friends and who are their enemies.”

We do a disservice to all those who have fought against this horrific system when we forget, or do not learn, our history. When we believe the state in its absurdist claims of loving and cherishing the people, of protecting our rights, we dishonor all those who have fought and died for liberation. A people’s history shows us who we are as it shows us what the system is, in practice, not in polished aphorisms. We must not forgive this nation-state for its lies, its violent deception, its terrorism, its crimes against humanity - from its genesis to today. We must not forget.

It is our mandate to learn and to tell the people’s histories, not just because it does service to those who have gone before, but because we cannot understand our present without telling our history. And we cannot carve a beautiful future from a morbid present unless we know where we are, who we are, and what we’re up against.

I greatly recommend reading the closing remarks by all of the Haymarket 8. They could just as easily have been uttered in a courtroom in 2025 as in 1886.