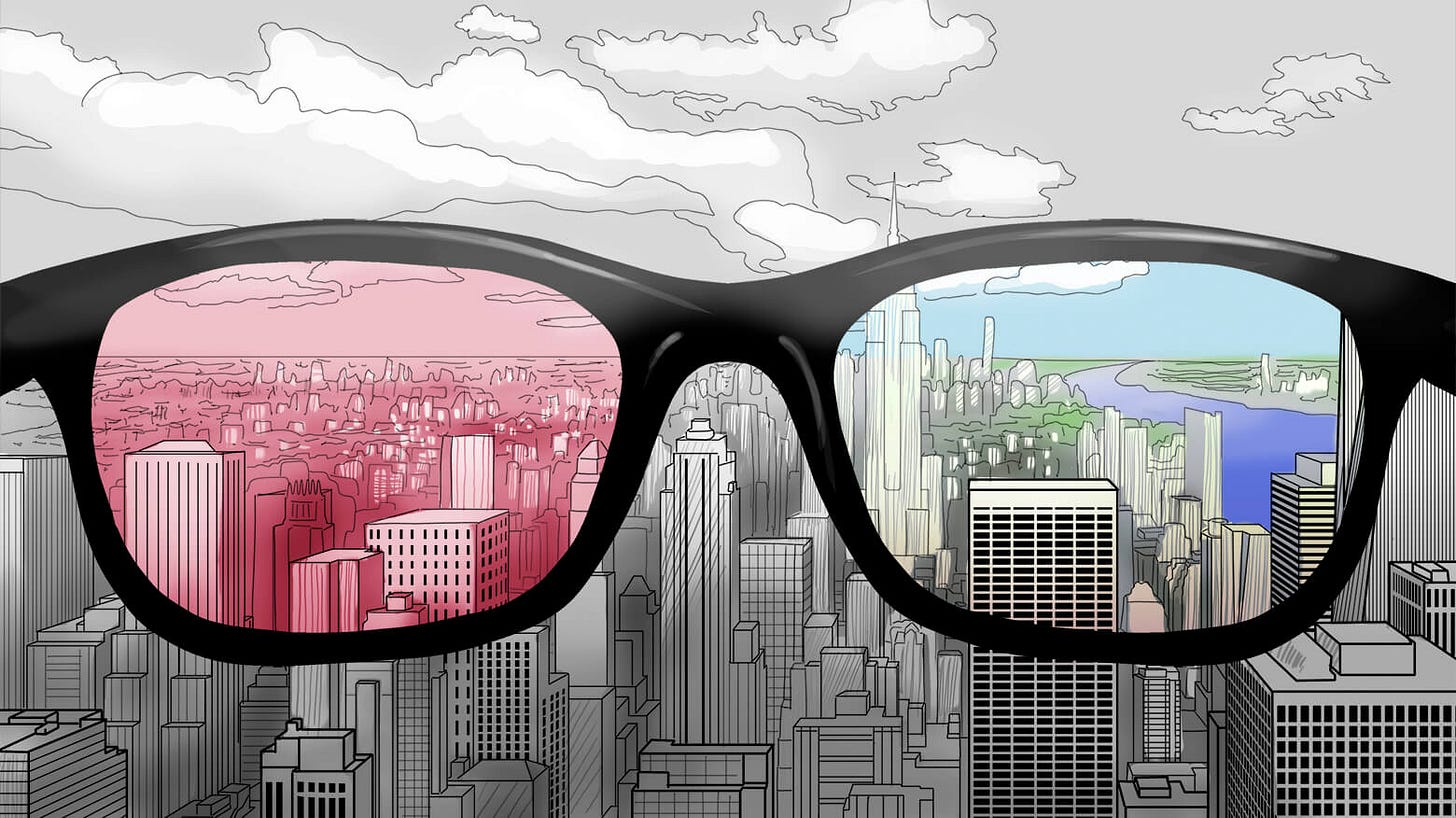

Lenses for "Reality"

on truths rather than Truth.

We don’t see reality.

In a 2018 interview for my news program Act Out!, cognitive scientist and author Donald Hoffman outlined this point in that easy kind of professorial way that both invites and dares one to marinate in the depth and breadth of such a comment. “I focus on the effects of natural selection and found that they’re uniformly against the Truth.” In other words, we don’t see reality because if we did, we wouldn’t be able to address the basic needs of our survival, from finding food to having sex.

Hoffman likened it to a computer desktop. If we actually saw the computer as it is rather than the pixelated representations of this folder, that icon, etc, we’d never be able to use computers efficiently. What we see, therefore, is a representation built by our brains in order to be able to survive in reality.

When I asked him about whether or not this means that we can even talk about anything being objectively true, he gave me another desktop example. If you drag a folder of documents into the trash and hit delete, that’s still a representation of the action. You’re not seeing the action itself. But you still lost those documents. So what we’re seeing f.ex with climate change is a filtering of reality through the human lens which we have access to. And although that lens does not allow us to see the whole Truth, what we are seeing is true, and it’s still very much killing us and countless other organisms. In short, we exist in reality and are subject to its shifts and variations, even when we don’t (and can’t) see that reality.

Me being a human and an organizer, I immediately folded his words into my perspectives and my work. First off, this once again proves to us the core idea that many oppressed have tried to point out for ages: even when you don’t see it, it still affects you. For instance, white supremacy is a white people problem. Even when you don’t see black people being brutalized or caged, Indigenous peoples brutalized and continuously colonized, migrants being caged and brutalized, these actions affect you. To quote James Baldwin, “We have yet to understand: that if I'm starving, you are in danger." Even just from a self-serving perspective, through an individualist lens, this problem that you don’t see is very much your problem as it indicates a system that in its core functioning does not value life, which can’t bode well for anything alive when push comes to shove. Of course, from a human perspective, the fact that your desktop is soaked in the blood of your neighbors should be of concern. But alas, for some it isn’t, so we go with the self-serving argument.

In a recent interview with Dr. Kim Wilson and Maya Schenwar, we discussed the book which they co-edited, We Grow the World Together: Parenting Toward Abolition. In our discussion, Dr. Wilson pointed out that “The intensification of suffering that we’re currently experiencing, the rise of fascism and all of the different things that we’re seeing, all of the reproductive justice issues and all the rollbacks and erasure of all of these things, we can look at what has happened in prisons and many people have been okay, absolutely okay with it happening to certain people.” In other words, prisons have been the canaries in the coal mine for the stark disdain our system has for basic human rights and life in general. The system’s done a good job of hiding those truths from us, but if we look for them, find the reports made by prisoners, former prisoners and their accomplices on the outside, there they are. And when we pick up those lenses and place them to our searching eyes, we see a system that is not and will not hesitate to abuse, oppress and deny basic human rights to anyone they deem lesser than, and the criteria for that is always at their discretion. And so it has always been.

You need only look at the history of the United States to see that the rights we think we have, we really don’t. As Ben Price, Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund’s education director put it in a recent Project Censored interview, “where we are today is not a perversion of what the promise of America was in the Declaration of Independence. It is actually a continuation of principles that were laid down.” The system was built for wealthy, white, property-owning (that’s human property as well) men. If people are shocked at these current times, it’s only because they’ve been looking at our place and time through the lens of American exceptionalism mythology, the land of the free bullshittery. When you use the lenses of a people’s history of the United States, you see that we were never meant to be free, something I dig into a bit more in my recent post, Tell My Story.

The people’s lenses are of course myriad, and they speak to the second understanding that Hoffman’s findings nourished in my mind: even if we can’t see an objective Truth, there are many things that are true. As one Syrian woman said of the violence and propaganda ripping her home place apart: “everyone may be lying, but the war is real.” As a journalist, this to me then suggests that we have to go to the roots to get the truth(s).

I have a longstanding bit about how objectivity is a myth. Biases are inherent based on our upbringing, our lived experiences, where we are geographically, in time, etc. With regards to journalism, I like to use the example of rain. Let’s say it’s raining. Well, that’s a weather report, and a pretty shitty one at that. Your job as a journalist is to build a story. So, what’s your pitch? Are you covering how the rain effects the billionaire whose sundeck party on his yacht now has to move inside? Or are you talking to the unhoused person whose belongings were washed into the drain? Are you talking about how this much rain is an effect of climate change? Every angle you choose betrays your bias. And there is no story without an angle, because the angle dictates who you talk to, what questions you ask, where you go, what you share. And that’s all totally natural. There’s actually nothing wrong with having biases because in fact, you can’t not. Even the apathetic have chosen to be apathetic, a bias of dumbshittery that we can get into another time. The problem with biases is when you try to hide them, like our corporate media and lots of journalists and journalist schools do. They claim that there are no lenses, and in so doing passively choose the lens handed to them by the powers that be. They become the useful idiots of the system, stenographers for the State Department, unthinking, unquestioning supporters of the oppressive status quo. And that does not a good journalist make. It doesn’t make a very good human either to be honest.

We are surrounded by a reality that we cannot see or objectively experience. How we choose to interact with it, relate to it, process it actively changes that reality - creating a cyclical mutualistically entwined system, a system that we have been a part of since life first unfurled on this Goldilocks rock. And since humans have existed, since we started organizing ourselves into groups, since those groups started to have variations in structure, started building cultures based on surroundings, internal and interpersonal dialog, we have constructed, passed on, buried, unearthed and refurbished lenses for our very subjective realities. We have carved truths into walls, scribbled them onto parchment, shouted them into crowds and into the void. We have also created myths, painted over lenses with opaque isms that don’t allow us even to see the desktop reality that’s accessible to us. Recognizing our propagandization requires us to remove those opaque lenses and choose the transparent myriad before us, the lenses made up of truths we haven’t considered, that we have lived but not understood, and that we have neither lived nor understood. This is not only then about recognizing our propagandization but doing something about it: setting down unsteady but sincere planks across the chasms of separation carved by a dividing and conquering system, considering the lived experiences, the truths that we’re missing because again, it’s your problem, and finding connections between those lived experiences (aka “issues”) that act as the planks against rupture.

For example, it’s drawing connections between the incremental genocide and occupation in Kashmir, the ethnic cleansing in Armenia, and the Armenian quarter of East Jerusalem, and the genocide in Gaza by looking at these issues through the lenses of the Kashmiris, the Armenians, and the Palestinians. You could of course see each of these through the lenses of India, Azerbaijan and Israel respectively, and as receivers of corporate media drivel, we do. But what biases does that prop up? What angle, what lenses are we using? And for what purpose? Who are we serving with that angle? Who do we want to serve?

It seems trite, and frankly obvious to say it but if we actually want a world where everyone thrives, we have to look at suffering from the perspective of those suffering. As philosopher Hannah Arendt once put it, “No one knows the rain better than the person who is stuck outside without an umbrella.” It made me smile to learn that this Jewish sister from another mister and another time had thought of the rain metaphor decades before I was born, and that I picked up on that without knowing she’d ever written it. But when you think about it, it’s not so odd that we would share that metaphor when we share many of the same lenses for “reality,” the same windows into the truths of our time, in the hopes of a future with better collective truths.

Brilliant. Thank you.